As this series of posts about SharePoint 2010 with Rights Management moves on, it moves further from SharePoint. In this post I’m describing the final steps in the RMS protection process, where RMS authenticates the requesting user and authorises actions with RMS-protected content.

In most configurations, RMS will rely on its internal AD Cache to reduce the number of LDAP queries for user attributes or Active Directory group membership. RMS typically queries this cache when users request a license. If RMS finds a matching e-mail address for a user, the allowed rights will be granted in a Use License, which will persist inside a document or on a user’s machine until the rights expire. LDAP queries are only issued if cached values don’t exist or if they have expired. After an LDAP query is issued, the response is used to process the immediate request and the values are stored in the AD Cache for later use.

Although this caching process should “just work” initially, there are a number of tiers where user information can fall out of sync. First and foremost, does the signed-on user have an e-mail address in Active Directory that matches the SharePoint User Information List? What happens if this e-mail address changes, or if it didn’t match initially? How can we invalidate stale AD Cache values? How long does the AD Cache persist? What’s in it? What needs to be considered when turning it off? In many cases the default AD Cache values will be suitable, but operational processes should be orchestrated with AD Cache settings in mind, whatever they may be. Cache invalidation processes should also be understood before they need to be invoked. I will explore these considerations in more detail here.

Posts in this Series

SharePoint 2010 On-Premises with AD RMS:

- Part 1 – Protecting SharePoint 2010 with Information Rights Management

- Part 2 – How SharePoint 2010 Finds and Updates a User’s Work E-mail Address

- Part 3 – How SharePoint 2010 Authentication Provider Types Alter the Initial Population of Work E-mail Values

- Part 4 – Inspecting an AD RMS Request from SharePoint 2010

- Part 5 – RMS Publishing Permissions for SharePoint 2010 Application Pool Identities

- Part 6 – RMS AD Caching for SharePoint 2010 Users

- Part 7 – RMS Use Licenses, Offline Access and Rights Revocation with SharePoint 2010

- Part 8 – SharePoint 2010 with AD RMS Process Diagram and Summary

Planned posts, covering newer versions and new twists:

- SharePoint 2010 with Windows Server 2012 AD RMS

- SharePoint 2013 with AD RMS

- SharePoint On-Premises with AADRM

- SharePoint Online with AD RMS

- SharePoint Online with AADRM

- SharePoint with RMS Trusts including ADFS

- Search, Rehydrated Users and RMS

How the RMS AD Cache relates to SharePoint

The RMS AD Cache is a store of point-in-time Active Directory user and group information. For the RMS protection process to work in a changing environment, it’s important that this point-in-time is aligned with:

- A user’s e-mail address information in the SharePoint User Profile Service Application.

- A user’s Work E-mail address in all User Information Lists for the Site Collections that they can access (which generally assumes that the user will be targeted by the User Profile to SharePoint Synchronisation Timer Jobs, as discussed in an earlier post).

If the AD Cache falls out of sync with changing AD data, we will need to flush it or wait until the cached values expire. Ideally these synchronisation processes should be aligned to ensure a good user experience and a known operational context. This alignment should include remedial steps to make sure that all three AD-dependent stores become current if escalated situations require administrative intervention. I’m comfortable assuming that RMS-protected content is “important” (worthy of RMS protections), so I’m going to extend that assumption and assert that “important” people might require escalated cache invalidation.

What is the RMS AD Cache?

Technically, there are two RMS AD Caches. One is in-memory on RMS web servers and the other stores values in the complementary RMS Directory Services database. These caches store Principal information (e-mail address, SID, and proxyAddresses) and Group membership (although this doesn’t pertain to SharePoint until 2013, which I plan to speak to in a later post). The in-memory cache and the database cache each have their own limits and duration settings, allowing for some flexibility when balancing freshness and optimisation.

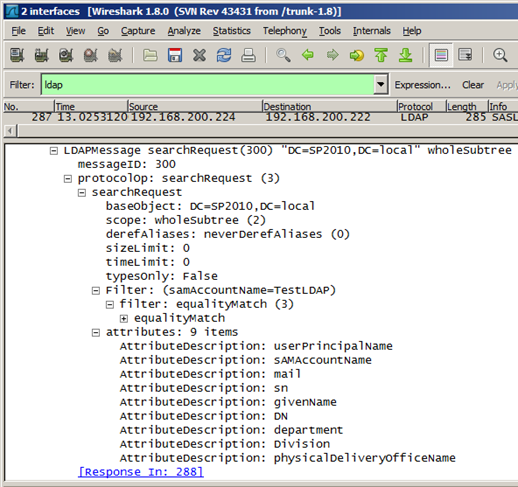

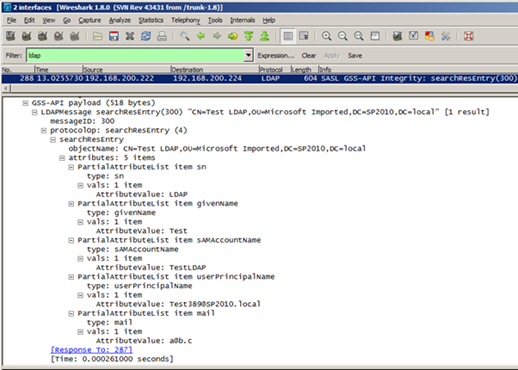

When a user logs on to RMS for the first time (or once cached information has expired), the RMS web server issues an LDAP Global Catalogue query to find “Principal Alias” information for the logged on user’s SID, and stores those values for the duration specified in the cache settings (12 hours by default). This is step seven from my Inspecting an AD RMS Request from SharePoint 2010 post:

An RMS Global Catalogue Query and Response

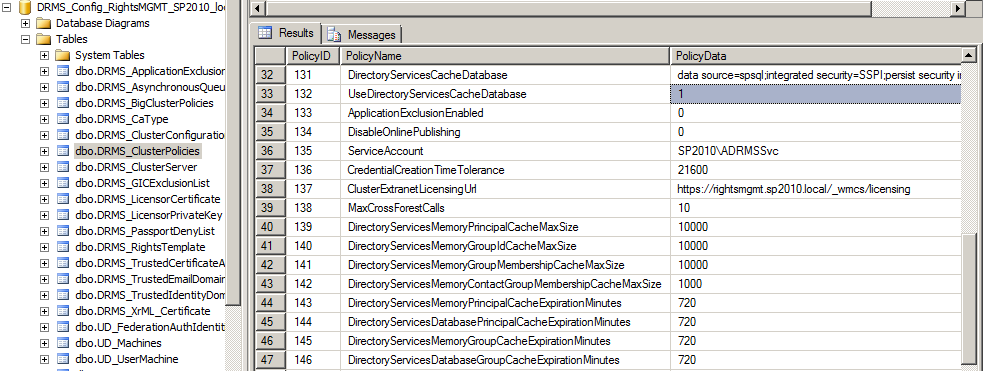

The RMS AD Caches are controlled by setting values in the DRMS_ClusterPolicies table in the RMS configuration database. For instance, the UseDirectoryServicesCacheDatabase row can be set to zero to disable the database cache altogether. Alternately, we can specify the expiration lifetime of cached values in RMS web server memory or in the Directory Services database:

…and we can specify the maximum size of the in-memory caches with these DirectoryServicesMemory<xxx>CacheMaxSize rows:

DirectoryServicesMemoryPrincipalCacheMaxSize

DirectoryServicesMemoryGroupIdCacheMaxSize

DirectoryServicesMemoryGroupMembershipCacheMaxSize

DirectoryServicesMemoryContactGroupMembershipCacheMaxSize

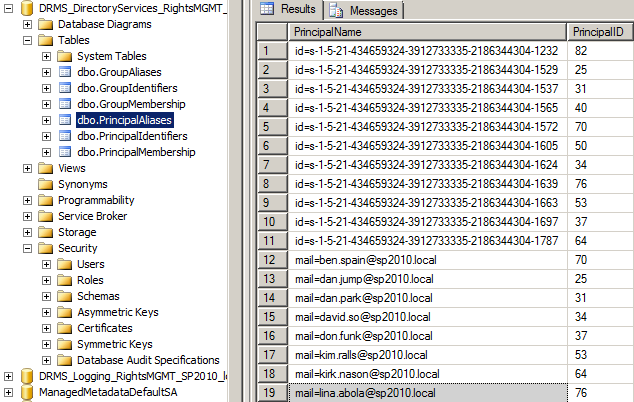

The database-cached values themselves reside in reasonably self-explanatory tables in the Directory Services database.

How Does the RMS AD Cache Behave?

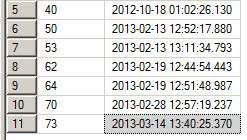

When a user accesses RMS for the first time, or if a previous Principal cache entry has expired, new PrincipalIdentifiers and PrincipalAliases rows will be created, the old rows will be purged and the Principal Cache Expiration time will be set to 12 hours in the future (by default). In this example I logged on to RMS with a user for the first time at 1:40 AM on 14/3/2013:

For the duration of this twelve-hour window, RMS will refer to the cached e-mail address information that was written to the PrincipalAliases table when the cache entry was created. When the window expires, the process repeats, and any information that’s changed should be reflected. Remember, it’s this e-mail address that must match the values in SharePoint’s User Information Lists. When an e-mail address changes in Active Directory, there’s a risk that the RMS AD Cache might mismatch the e-mail address that SharePoint publishes to. It’s possible (likely even) that the synchronisation from AD to User Profile and User Profile to User Information List will complete in a different window than when the RMS AD Cache value expires. The impact of this gap will vary depending on how frequently e-mail addresses change in Active Directory, how often SharePoint synchronises with Active Directory, how long the cache persists, and the likelihood of a user accessing RMS when the values are out of sync. In my experience, frequent changes to a user’s primary e-mail address are exceptional, but in some organisations they are routine.

If we take a severe step and disable the cache for these reasons, RMS will issue the Global Catalogue query as above, but no information will be written to or read from the cache database or memory and the Global Catalogue query will be issued at every login. It’s in this way that the AD Cache provides performance benefits. It significantly reduces the number of Global Catalogue queries for user information and group membership (the expansion of which can be particularly expensive).

Keep in mind that caching group expansion is often valuable for non-SharePoint workloads even if it doesn’t provide any benefits for SharePoint 2010 and earlier. The AD Cache settings should be configured to benefit all workloads, not just SharePoint. Herein we have a challenge to maintain supportability while retaining desirable optimisations. Perhaps the best compromise for an organisation with frequent e-mail address or group membership changes would be to cache for less time – perhaps one or two hours rather than twelve. These performance and support impacts should be assessed before making changes in a production environment.

Flushing the RMS AD Cache

In escalated situations, it may be necessary to flush the AD Cache in order to restore access before the cache expires normally. In this case, setting the ExpirationMinutes and MaxSize values to 0 will clear the memory cache (or this can be achieved by resetting IIS on the RMS web servers). Additionally, the UseDirectoryServicesCacheDatabase value should be set to zero. Once these changes have been made, you may notice that this doesn’t change any values in the database cache – RMS just stops referring to that information. When/if it’s re-enabled, the old database values will be referenced if they are still valid and new values will be written normally.

For a number of reasons, I would recommend flushing the cache only in exceptional situations. We are directly writing to a production SQL Server table when we make these changes (unless we come up with a more manageable approach), and the performance impacts will be felt for all users until the cache is re-enabled. Ideally the agreed expiration windows should be set appropriately from day one, to a duration that will be acceptable when SharePoint and RMS fall out of sync, while retaining some optimisation for all RMS-protected workloads.

NoRightsCaching with SharePoint

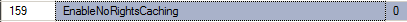

In addition to caching user attribute and group membership values, we can control whether RMS caches denial of access with EnableNoRightsCaching.

The No Rights Cache is not documented well, but I’ll take a stab at filling that void. It’s an in-memory cache that stores rejected access for 12 hours. Jason Tyler mentions it in a few of his blog posts, and that’s about it:

“…and before you ask EnableNoRightsCaching is new to ADRMS. It caches ‘No Rights’ failures, so that we can quickly tell a user who keeps trying to open content they don’t have access to ‘You’ve already been told you don’t have access, punk!’, without making a round trip to the DC again.”

…and:

“…causing your ADRMS server to become angered and add your recipeints to the “lump of coal” list it secretly stores in memory (EnableNoRightsCaching), until its default 12 hour temper tantrum is over.”

Note: I haven’t tested this extensively myself, so please apply all the normal caveats if relying upon my assessment here.

In the majority of situations, caching denial of access should only cause problems for SharePoint users if their e-mail address has fallen out of sync with RMS. For SharePoint content specifically, RMS should only deny access as an effect of identifying a user, rather than because the user is unauthorised. SharePoint publishes RMS-protected content to the requesting user on-demand, based on the rights that have been granted in the SharePoint list. This is fundamentally different to the protection process when a file server user selectively specifies RMS rights on top of normal file permissions. In other words, SharePoint users should not be blocked by NoRightsCaching since they should always have rights in RMS. If the user doesn’t have rights in SharePoint, the request for RMS-protected content will never get past SharePoint.

However, we still need to consider what will happen if RMS denies access to a user that cannot be identified (because of e-mail address misalignment between SharePoint and RMS). The effect of operating RMS with NoRightsCaching is that SharePoint users may need to wait for the No Rights cache to expire if they’ve been blocked by it, or it could be temporarily toggled off to allow a user to acquire licenses. In fact, an IIS reset should do the job, since the cache is in memory, but this should be exceptional. When misalignment occurs, users would lose access with or without NoRightsCaching enabled, but if we are invalidating caches in an escalated situation then we have one further cache to think about before access can be restored.

None of this changes the decision to use the cache or not. It just means that the outcome will have a lower impact in any case. There will be fewer NoRightsCaching hits since SharePoint is primarily responsible for authorisation, before the request redirects to RMS for the secondary rights checks. Similarly, the number of user information misalignment issues that require an extra step to solve should be few, assuming e-mail address changes are relatively infrequent, or on the assumption that we’ve already ironed out this remedial e-mail address misalignment process because we need to do that anyway. All told, I feel that this setting should typically be set for requirements outside of SharePoint, particularly if mitigating DDoS attacks is important, although if e-mail addresses change a lot then it may be compelling to disable this cache, for SharePoint and non-SharePoint workloads.

I can think of one exception to this, if SharePoint list settings allow a user to Save As (or “Export”) a document. In this case, the document could be transmitted (intentionally or otherwise) to another user. This new user would then need to request a Use License from RMS in order to work with the content, which would be allowed or denied normally by RMS (and not by SharePoint), depending on whether they’ve been granted access by the offline “owner” of the document. If there were potentially many bad requests for content that has been taken offline from SharePoint, then NoRightsCaching could be useful, but only because the information is no longer managed by SharePoint! Indeed, this illustrates why it’s often undesirable to allow users to export RMS-protected SharePoint content. This option effectively allows users to opt out of the information management lifecycle and all other intended governance. In a similar way, if users upload RMS-protected content to an unprotected SharePoint list, the same considerations apply.

RMS AD Cache Planning

To sum this up, we have a number of options to optimise RMS Global Catalogue queries by caching results in memory, in a SQL Server database, or both. It’s unequivocally good that we have these options, as they can be disabled if necessary. Otherwise, they provide us with control. A probable outcome is that we might consider adjusting the default cache values to specific, organisation-wide, cross-workload requirements.

When coming up with starting values, it’s worth considering that:

- You don’t want AD RMS to become a performance bottleneck. There’s already quite a bit of hopping around between browser, Office client, SharePoint and RMS.

- The RMS AD Cache settings have a more acutely-felt impact outside of the SharePoint world (or at least before SharePoint 2013), where Group Expansion “cost” can be significant. These AD Cache settings have an impact on all uses of RMS, not just SharePoint. If the cost of expansion is significant enough, it could even become a capacity planning consideration for the Global Catalogue servers that RMS queries.

- E-mail address change processes should be orchestrated with the impact on SharePoint and RMS in mind. Arguably, the SharePoint User Profile and User Information synchronisation intervals should be aligned with RMS AD Cache expiration values, although things may not work out quite so elegantly with all things considered.

- NoRightsCaching should usually be configured for the requirements of RMS as a whole (such as DDoS mitigation) or for specific NoRightsCaching requirements from non-SharePoint workloads.

Even if there aren’t many one-size-fits-all answers among these planning considerations, I hope this overview provides some clarity for discussions between SharePoint and RMS administrators, as most available documentation today is mutually apathetic.

I enjoyed this series of post. We are looking into setting up ADRMS with a SharePoint environment and I wanted to learn how this will effect SharePoint development, usage, and security. These posts answered a majority of the questions and provided new ones. One major question that I can not find an answer too is how does ADRMS work with office web apps in SharePoint 2010. We are looking for the ability to force users to view the documents in the browser without being able to save or print. I know SharePoint can make it so that documents cannot be downloaded taking care of the save option however, cannot find a way to keep them from printing. We know the risk with copying and screen capture and willing to accept that limitation.

All that being said do you know if ADRMS kicks in when a document is opened using office web apps and viewed in the browser. If not is there an option to force the document to be viewed in the browser that works with ADRMS and SharePoint.

Additional Information:

SharePoint enterprise 2010

Office 2010

Web Apps installed

I’m the SharePoint Admin and I’m just starting to learn ADRMS

Hi, thanks! In brief, there is no Office Web Apps support for IRM in 2010, and generally speaking, if Rights Management is your aim, you will want a full client. Since SharePoint enforces Rights Management at a document library level, you have an opportunity to align these policies with how users will open documents in them by setting the default opening behaviour appropriately.